IGALA PEOPLE: ANCIENT NIGERIAN INHABITANTS OF NIGER-BENUE CONFLUENCE IN KOGI STATE

The Igala (Igara) people are largely agrarian and semi-fishery and Yoruboid-speaking people located at one of the natural crossroads in Nigerian geography (east of river Niger), occupying the Niger-Benue confluence and and astride the Niger in Lokoja, Kogi state of Nigeria. The area is approximately between latitude 6°30 and 8°40 north and longitude 6°30 and 7°40 east and covers an area of about 13,665 square kilometers (Oguagha P.A 1981).

Beautiful Igala girl from Kogi State, Nigeria

The Igala tribe is among the great Iron-ore technology states that rose to power between 1400 and 1700 AD, alongside with the Benin, Nupe and Oyo empires. They have exercised a considerable influence on the surrounding neighbours. Igala forms a kingdom whose ruler, the Attah, has as his capital Idah on the River Niger. “Igala people are not toddlers. They are goal-getters in every positive sense of the term, never mediocres. In a nutshell, they are typical achievers, movers and shakers of history” (Egbunu 2001).

Igala man from Kogi State

Igala land begins at Adamagu a few kilometres north of Onitsha and continues up to a confluence, from where it protrudes linearly north-eastward along the Benue. It finally terminates at Amagede in Amagede at the eastern boundary, which is demarcated by the Idoma in Oyegede and Otupl and north Nsuka – areas of Enugu Ezeke, Itah Edem, Ururu, Adavi and Ogugu of the Anambra rivers. The two great rivers that divide what became Nigeria, place the confluence as one of the national and cultural regions which brought the Igala into contact with the wide range of people in Nigeria.

Igala elderly woman

The population of Igala land is estimated to be about four million, over 70% of whom are subsistence farmers. The Igala ethnic group is densely populated in their settlements around the major towns such as Idah, Ankpa and Anyigba. They are also found in Edo, Delta, Anambra, Enugu, Nassarawa, Adamawa and Benue States. However, the bulk of them are indisputably found in Idah, Ankpa, Dekina, Omala, Olamaboro, Ofu, Igalamela/Odolu, Ibaji, Bassa (and even Lokoja and Ajaokuta) Local Government Areas of Kogi State (Egbunu 2001,49).

Igala man with Igala traditional tribal mark

Varieties of people from different ethnic origins, speaking different languages live in Igalaland. The dominant group however are the Igala people themselves who are regarded as the most primordial of all identified groups that exist in the area today. Other ethnic groups include the Nupe, Hausa, Yoruba, Igbo, Tiv, Idoma, Ebira as well as immigrant from the Etsako Local Government Area of Edo State.

Kola nut (obi) of Igala people: http://ayedefilmandphotography.com/

Among the Igala people Kola nut (obi) is very important. It has socio- religious significance and is often eaten in socio-religious gatherings. Without it no traditional marriage can be celebrated in Igala-land. Its breaking and eating symbolize unity, peace, love and acceptance under the protective eyes of Ọjọchamachala (God) and Ibegwu (Ancestors)

Igala women in their traditional dress, USA

In Igala tradition, infants from some parts of the kingdom, like Ankpa receive three deep horizontal cuts on each side of the face, slightly above the corners of their mouths, as a way of identifying each other. However, this practice is becoming less common.

A woman with typical Igala tribal facial marks

Origin of the Name Igala

The first tradition says “Igala” is a derivative of the Yoruba name for antelope (Igala). So these school of though tries to suggest that there were many antelopes during the early migrations into the land giving rise to this name. The Yoruba word “Igala” means Antelope which is Ọchachakolo in Igala language.

This animal is noted for its fast steps. It is a pacesetter and frontliner. Of this animal, the Igala proverb refers, “Ọchachakolo Ẹla ki d’ọgba amomi ẹbun”, (Antelope, an animal at the forefront never drinks unsettled or dirty water). This point looks plausible, considering the fact that so many of the Igala villages were named after animals. For instance, Ojuwo-Ọcha (Antelope hill), Ugwọlawo (Guinea fowl’s bath), Ọbagu (Chimpanzee), etc. It is also related in some quarters that even a German Volkswagen company recognized the nature of this to the extent that they named one of their best cars “Igala Volkswagen” in the 1970s after it. But the second tradition is even far more tenable.

This second tradition is based on two premises:

That the Igalamela (nine Igala clans) are the autochthonous, first occupants of Idah (Igala) native town. About them, oral tradition says that they pushed the Idoma people to their present location in Benue state (from the present Idoma Street in Idah). This Igalamela chiefs are greeted “Onu-Igala” (Igala leader or chief) up till date.

That Etemahi is the leader (head) of the Igalamela royal lineage. “Ete ma hi” in Igala language denotes – “it is from the beginning (the roots) one can cook any edible object well”. An Igala adage goes thus, “Ẹtẹ ma hi ma m’ahi ọgbọ n” (from the beginning they cook and it would not be tasteless).

These are idiomatic expressions suggesting that the Igala race as developed (or tasty) as it is today evolved from this particular thorough roots, Odudu I chanẹ ichanẹ-n (Day break began in the morning, not in the evening).

From the foregoing, we can infer that the word IGALA is a compound word with “Iga” as its root and “Ala” as the qualifying noun. In Igala language, Iga means a partition, blockade, a dividing wall e.g. partition of India in 1947. And the qualifying noun, Ala means “Sheep”. This could imply that the first settlers in Igalaland (the Igalamela) saw themselves as God’s flock or sheep that eventually found their greener pasture in this location. They probably felt it was better to settle here. Whether they came from the Yoruba race or any other larger language group or whether they drove out any group of their earlier inhabitants (such as the Idomas) is not our immediate concern here. They came, they saw it was a fertile ground full of prospects and they settled here from antiquity. Period!

Perhaps, they made Iga-Ala Mẹla that is, making nine “sheep” apportionments, partitions, dividing walls or simply, fences against possible invading troops, as it was common in those days in search of a formidable security. They were then referred to generally as the IGA-ALA people. The name gradually metamorphosed from Iga-ala to IGALA as a result of the combination of the two vowels (a + a). The nomenclature then became IGALA. The name must have come in the figurative sense of people referring to themselves, as the sheep feels shielded and protected under its shepherd.

God (Ọjọ), is often seen by the Igala people as Ọchamachala (owner of the entire universe), Odobọgagwu (the all-powerful one), Anẹ-magẹdọ (the all-courageous one), etc.

Igala Owuna masquerade performing traditional dance

This sense of being protected under God’s shadow was extended into the naming of a certain street, UBI-IGA (behind the partition) in Idah, during the Benin/Igala War in A.D. 1515 – because of the partitioning against foreign invaders. Other parts of Igalaland are not left out in naming villages after their functions. For instance, villages which served as formidable fortresses against foreign invasion at a certain period of history or the other, had such names e.g. Iga-Ebije (iron partition), Iga-Ikẹjẹ (Ikẹjẹ’s wall); Igaliwo (Aliwo’s wall), Iga-Olijo (Adder’s wall), Igagbo (Agbo’s wall); Ig’ọjọ (God’s protective wall), etc. It is interesting to note that the Igas were practically erected in those days for defensive purposes.

According to oral tradition, the Odogo (ancient storey building) in Ata’s palace was used as a hideout. From there the soldiers had a full view far over and across the cliff near the River Niger. By this means they were able to detect enemy troops afar. A river is also believed to have changed its course or totally dried up around Ọkpakpala-Ukwaja. This river also served as another shied against enemies.

From the above, it is obvious that Igala people are people who feel highly secured under God’s umbrella. That is why in times of adversity, they would simply exclaim “Ọjọma” (God knows or God is in control). And if the Antelope Igala origin appeals to the reader more, he/she should know that Igala people are not toddlers. They are fast at achieving their goals. They are goal-getters in every positive sense of the term, never mediocres. In a nutshell they are typically achievers, movers and shakers of history.

Igala men

Environment/Geography

The Igalas have an unusually and richly endowed environment. They are within the “middle-belt” of Nigeria which has an advantage of the climate of the drier Savannah vegetation to the north and the wet forest regions to the south.

The area lies within the warm humid climatic zone of Nigeria. There is a distinctive wet season dichotomy. The wet season lasts from about April to the end of September or early October while the dry season lasts from about October to about the end of March or early April. Rainfall can be heavy and the effects of the harmattan can be severe, especially from about November.

The area has an average rain fall of about 50” a year. The lowland riverine areas are flooded seasonally, making it possible for the growing of paddy rice and controlled fish farming in ponds that are owned on individual or clan basis. The lbaji area is the major place awashed by flood. This makes the area very fertile soil more than other place in the land: “The receding floods leave behind a large quantity of fish in ponds and lakes. This facts, plays an important role in the economic and social lives of the people,”

Simply put, the vegetation is mainly deciduous, with the major rivers (Benue and Niger), a few minor ones such as Okula, Ofu, Imabolo, Ubele, Adale, Ogbagana, and many streams in the land. Hence, is Igalaland popularly known as a blessed fishing and arable region.

The most common economic trees are palm trees (ekpe), locust beans (okpehie). mahogany (ago), iroko (uloko), whitewood (uwewe) and raffia palms (ugala). Common plantations are of okra (oro..-aikpele), cashew (agala), banana (ogede). Some of the economic trees mentioned here provide timber for the people and for sale. In the forest regions were also found certain wild animals, such lions (idu), hyenas (olinya), leopards (omolalna or eje), elephants (adagba), bush-pigs (ehi), chimpanzee (ukabu). etc.

This favorable vegetation makes farming and hunting highly profitable. Thus. 90% of the population. practice farming. Both forest and savannah crops thrive on Igala soil very well. Thus, the main forest crops produced are: yams, cassava, maize, melon and groundnut. And they produce such savannah cereals as guinea corn. beans. millet and benniseed. However, due to the shifting cultivation being practiced, bush burning and felling of trees, a good proportion of the forest is being gradually destroyed and wild animals are fast becoming extinct.

Igalaland is blessed with rich natural resources. In the south are swamps where crude oil was prospected some years ago. It is generally believed that oil was discovered at Alade and Odolu. IS The Okabba (Adagio) coalmine is close to Ankpa in the north. The country has benefitted from the coalmine since 1967.

There are many roads in the area. The main ones are Anyigba-ldah, Anyigba-Ankpa, Anyigba-Shintaku. Those of Anyigba-Ajaokuta, Ankpa-Otukpo, Otukpa, Ankpa-Ogobia. Idah· Nsukka and Ejule-Otukpa link the land with neighboring states. Good waterways are possible between Idah-Agenebode-Onitsha and the Shintaku-Lokoja axis of River Niger. These waterways have served as veritable means of transport in the recent past. It encouraged social and economic interactions.

Today, Igala land does not possess any airport. However, air travelers make use of Ajaokuta Steel Company’s airstrip. The Itobe-Ajaokuta Bridge constructed about two decades ago on the River Niger has also turned out to be of tremendous benefit as it has enhanced intra and inter-state links and commercial transactions.

Language

Igala people speak Igala language, which belongs to the Yoruboid languages spoken in North Central Nigeria (Akinkugbe 1976, 1978; Omachonu 2000, 2002) which also forms part of the larger West Benue-Congo phylum (formerly part of Kwa).

As a result of the strong linguistic affinities, Dr. Femi Akinkugbe (University of Lagos) has recently classified Yoruba, Itsekiri and Igala as belonging to what he calls the Proto-Yuroboid sub-group in the main Kwa group.

Igala people

It is estimated that nearly 4 million people speak Igala, primarily in Kogi State, Delta State and Edo State. Dialects include Ebu, Idah, Ankpa, Dekina, Ogugu, Ibaji, Ife. The Agatu, Idoma, and Bassa people use Igala for primary school.

Although one may argue that Igala is unlikely to be so endangered in the proper sense of the word considering the number of its native speakers and linguistic researches available in the language (Armstrong 1951, 1965; Omachonu 2000, 2002, 2003a, 2003b, 2006, 2007a, 2007b, 2008; Atadoga 2007; Ejeba 2009; Ikani 2010), one of the aspects always identified as being so seriously endangered in the use and study of the language is the numeral system (See Etu 1999, Ocheja 2001). This is because children nowadays rarely know how to count in Igala. Even adults, mix up Igala with Hausa and English when they count money and other objects in the language. A similar scenario was pointed out by Atóyèbí (n.d.) of the numeral system of Ọkọ which he described as the most endangered aspect of the language because the act of counting in Ọkọ, according to him, has been left to older members of the community with the younger generation preferring to express numerals in the English language

instead.

History

The actual origin of the Igala people is not quite known. Different people present many versions of legends of immigration There are claims, for instance, that the Igala people came from the Jukun (Kwarara/a), some says Benin, others Yoruba. Yet, others feel they migrated from Mecca (Southern Yemen) or Mali.

In the past, the reigning Atta, His Royal Majesty. Agabaidu (Dr.) Aliyu O. Obaje, had. for instance, explained: "the !gala came from Southern Yemen, passed through Ethiopia (where there is an ethnic group called the Gala) and through the (medieval times} Empire of Mali, to Jukun land; then finally, to our present location." In another instance, the Atta said that the Igala "came from the Arab country of Yemen and were in the present Nigeria at the same time as the founding fathers of the Yorubas, the Jukuns and the Beriberis or Kanuris Bornu. He also maintains that the earlier migration into Igalaland was at "about the 12th century A.D.... led by Amina, a Zaria princess and warrior. who fought her way to Idah ... with Hausa and Nupe followers.

Certain traditions even hold that the Igala are of Fulani origin, simply because of the similarities in their physical features. It IS clear that Fulanis do not speak a Kwa language. And owing to the linguistic affinity, others affirm the Yoruba connections. For Byng Halt notes that, "It is not surprising that within a short period of arrival in Igala land, a Yoruba is well acquainted with the language.” He attributes the ease in learning the language to the closeness of the two languages. Armstrong sticks to this same view when he said: "the most definite historical statement that can be made about Igala is that . they had a common origin with the Yoruba and that the separation took place long enough ago to allow for their fairly considerable linguistic differences. There is a whole corpus of oral traditions on the origin of the Igala people.

While this study did not engage .in any detailed criticism of the diverse opinions on the Igala origins. it gave a thorough look: at certain .inescapable facts, These intricate issues were pin-pointed in order to allow us take a solid stand.

The view that Princess Amina of Zaria led the very first migration into Igalaland in the 12th century does not hold water. This is because Queen Amina was a 14th C figure and history has it that the Igala people were already settled in this area and were relating socio-culturally with the Igbos right from the ,7th and 9th century A.D. Moreover, the obvious absence of a legend relating to this princess and warrior .in Igalaland is a clear indication that it might not be true afterall that she actually reached Igala land. Stories on Igala Benin war and Igala-Jukun war, for instance. are very popular. The near dead silence on an Amina war leaves room for great doubts. Niven argues against the presupposition that she died at 'Atagara' (that is ldah) when he said: "she died at Atagara, probably a place iii the Gongola valley then under Kwararafa, not Idah. which is now known as Atagara.'

The linking of the Igala with Yemen In Arabia is another highly speculative opinion. This story was probably a device of the Muslims to Islamise Igala people. The people of Igala had long settled before the Galas entered Ethiopia. because tradition has it that it was only in the century A.D, that the Gala migration to Ethiopia took place. In addition, it is quite improbable that the Semite Galas would metamorphose into Negroes of the contemporary Igalaland overnight. The similarity in name is thereby merely coincidental.

The Mali connection remains baseless too because the similarities between the words "Mela" (nine of them) of Igala-Mela (the nine Igala kingmakers) is in no way attributable to “9” as originating from Mali. To the Igala mind, "nine" simply symbolizes perfectness.

Likewise, the supposition that the Igalas came out of the Fulanis, carries no weight, since "no tradition in Igala supports it. History attests to the fact that the Fulanis were still in the region of Senegal by the time the Igala were already having a "centralized state system ... in the 12" century.

That the Igala have a traditional link with the Benin kingdom is indubitable. There abound theories for instance, that support a Benin origin of Igala kingship. However, there was already in existence indigenous Igala people with their kingship systems before the arrival of the Benin kings. But it must be understood that at some stage of Igala history, the Benin people wielded some power of influence over them. The difference in their system of government alone is enough reason to prove that it is never true to say the entire Igala originated from Benin.

The tradition, which holds that the Igala has the same origin with the Yoruba seem to be a plausible one. This humble submission is based on the fact that the Igala language has a lot in common with the Yoruba. Okwoli supports this view when he said: "When people speak the same language. or related languages, there is every reason to believe that they have common origin or have met somewhere.

The Jukun link with the Igala is another very strong tradition that immediately calls for serious attention. Stories about the Jukun origin of Igala kingship, for instance, cannot be waved aside. That there were certain Jukun immigrants who came among the Igalas at some stage of the development of the Igala kingdom is quite evident It is even a common knowledge that the present ruling dynasty is Jukun.

Ultimately, therefore, there is no single account of the origin of the Iga1a people, which is unassailable However, one may agree with Boston that the different tradition "probably correspond to different phases of history in which the Yoruba link may be the most ancient, followed by the Benin connection, and most recently. some form of Jukun suzerainty'. In order not to continue swimming in this shark-infested waters of legends and traditions, we concluded that the Igala kingdom originated from within their immediate vicinity, namely. West Africa. As a matter of fact, before the advent of the colonial masters, about seven very prominent black. kingdoms were noticeable in the forest belt, thus, Ashanti, Dahomey. ]fe, Oyo, Bini, Igala and Jukun(Apa) kingdoms.

Social Organization

The social organization is essentially kin-based. The nuclear family is the smallest social unit but this is inseparably tied to the extended family system involving the linage and the clan. All members of these extra nuclear-family units regard one another as “brothers” or “sisters”. A number of agnatic families combine to form a clan and number of them may constitute a hamlet or even village. Often the members of such hamlets or villages trace their origin to common apical ancestors. The sociological arrangement is, itself a factor that promotes unity and peace among the people.

Igala woman

Political organization

The political organization is concerned on the monarchy, headed by a paramount king, the Attah-Igala, who is regarded as the father of all Igala people. Attahs of old wielded a lot of power and authority and established a very powerful kingdom possibly dating to about the 8th or 9th century AD. At its apogee, perhaps in the 16th century, the Igala kingdom did extend far and wide to include parts of Igboland (Nsukka Area) to the south Koton-karfe (including and beyond area of north Kogi) to the north; part of western Idoma land to the east (including Igumake) and parts of Etsakor in the west.

OGUGU IN FOCUS: HRM, Agaba Idu, AMEH OBONI II storms Oguguland tomorrow

as part of the 2014 Royal Tour. Amoma Ogugu me Kwane k'ojane Igala

ki'nyogba Efuredo, Ufedo kpai Udama!

Influences of the Igala, operating from the headquarters at Idah, were also felt at Nri-Igbo-Ukwu and Onitsha in Anambra state; among the Nembe and Kalabari on the Atlantic cost; as Asaba and among Nupe in present day Niger state where an Igala prince, tosede or Edgi is acclaimed to have established the Nupe kingdom. Wars were fought, peace treaties were concluded, tributes were paid and trade organized with these and other people. Wars for instance were fought with the Jukun of Kwararafa in present-day southern Taraba State and with the Bini during the reign of Oba Esigie 1 in (1515, 1516 AD) as recorded in Portuguese in Lisbon today.

The glorious era of Igala kingdom was disrupted with the effective colonization by the British of the area now known as Nigeria from about 1890, with the amalgamation of the Northern and Southern Nigeria protectorates in 1914 (by Col. Frederick Lugard) the British policy of what is now known as Nigeria, where established monarchs were used to rule their own people “indirectly”. Thus the power of the kings and chiefs was gradually eroded until they become puppets in the hand of the British. There was resistance here and there, for instance in Opobo (by Jaja), in Itsekiri land (by Nana), in Benin (by Overanwen), in Sokoto (by Sultan Attahiru) and in Igalaland (by Prince Atabo Ijomi later, Ata-Igala from 1919 to 1926); but in essence, the traditional rulers lost the battle.

Native administrators were established (somewhat along geo-ethnic lines) and the monarchs were made tutelary heads of the administrations, while the British acted as the real administrators and decision makers. In this vein, the Igala native authority was administered as part of Kabba province so even after the independence in 1960.

HRM, AMEH OBONI II, Agaba Idu, Ata Igala.

With coming of the military in 1966, and with state creation in 1967, Igalaland became the eastern part of a Kwara State (initially named Central Western State) when a twelve state structure was created. When a new nineteen-state structure was later created out of the 12 in February 1976, Igalaland was carved out of Kwara and merged as the Western part of a new Benue State. In August 1991, itinerant Igala found themselves in a new state, Kogi which is where they are now.

Idah remained the cultural headquarters of Igalaland and the political capital of Idah Local government Area. In 1968, Igalaland was split into three administrative units for the sake of conveniences. The units – Idah, Ankpa and Dekina were administered as local governments, later (in 1976). Dekina division was itself split into Dekina and Bassa, again local government areas were carved out of Ankpa while Ofu was carved out of Idah. Today, Igalaland harbours nine local governments out of the 21 local governments in Kogi State.

Igala man in his traditional groom dress

The Igala Traditional Council

There used to be one Igala traditional council headed by the Attah. Later, with the creation of autonomous local government area, and Ankpa traditional council headed by Eje was created. A Bassa Komo, Bassa Nge and the Ebira Mozum Districts with its headquarters at Oguma was also recognized. Dekina and Idah remained under the umbrella of the Igala traditional council headed by the Attah-Igala. In the present dispensation, each local government council in Kogi state has its own council of Chiefs and everyone recognizes the pre-eminence of their respective premier monarchs – the Attah-Igala, the Ohinoyi-Ebira and the Obaro of Kabba.

Igala men

The Igala Monarch

The Igala Monarchy, one of the oldest and one of the most formidable in the central Nigerian area is central around the person and office of the Attah-Igala who is regarded and treated as the father of all Igala people. The remoteness of the Attah institution has not been properly determined historically but oral tradition and archaeological records point to dates around the 8th and 9th century AD.

HRM, AMEH OBONI II, Agaba Idu, Ata Igala.

The possible influence of the Igala kingship on Nri and Igbo Ukwu cultures, the latter of which has been dated to about 8th and 9th century AD by Professor C. Thurstan Shaw, shows that if Igala monarch influenced Igbo Ukwu’s at that period, it could be suggested that origins and history of Igala culture may well pre-date the 8th or 9th century AD (Shaw, C.T. 1970, Igbo Ukwu, Faber, London).

Oral tradition state that some Attahs whose period of reign cannot be determined chronologically reigned over “Igalaland” for quite some time. These include Agenepoje, Abutu-Eje and Ebole Jonu. This is however a very shady period of Igala monarchial history, the length and remoteness of which are yet to be ascertained.

The Special Jumm'at Prayer led by the Chief Imam of the palace, Alh. Idrisu Liman... HRM, AMEH OBONI II now resumes office for the day's tasks.

But after the proto-dynastic period, emerged a period where oral tradition is much more reliable, that is the period of Ayegba Oma Idoko who is the founder of the present quadrilinear dynasty. Thus the descendants of Ayegba headed by Akwumabi, Akogwu and Ocholi have produced the Attah Igala in succession to one another over the years. Later however, the genealogy of the Akwumabi dynasty was split into two, headed by Ame-Acho and Itodo Aduga, thereby creating a four dynasty structure as shown in the scheme below (note the figures after each name show the tenure-ship from Ayegba Oma Idoko.

HRM, AMEH OBONI II, Agaba Idu blesses the Royal Palace Singers before proceeding for the day's job... Achebe!!!

The Atta’s scope of influence

With Atta Ayegba Om’Idoko, the kingdom was zoned in the 17th cetltury A.D. into smaller units in order to decentralize authority. Then in 1905 the British created the districts. These districts comprised Ankpa, Dekina, Egwume., Ejema, Imane. Iga, Ika, Ogwugwu, Ojokwu. Atabaka (Okpo), Biraidu (Abocho), Ife (Abejukolo). Odu, Iyale, Emekwutu, Okenyi, Ojokiti, As these districts were formed and “trustworthy relatives and followers” were sent to rule, these were given the ‘traditional titles of “Onu” (the principal person or chief).

Some Igala tradition holds that an Atta gave the Nupes a Kingdom, He bestowed the rule of Nupe country to Edegi (Tsoede), one of the sons he had from a Nupe mother. He gave riches of various types to him and gave him different insignia of kingship: a bronze Canoe, twelve Nupe slaves. the bronze Okakachi (Trumpet) which are still being used by Northern Nigerian ~.state drums hung with brass belts and heavy iron chains and fetters which were endowed with strong magic power …, Tsoede or Edegi then became the ruler of the Nupe people and took the title of Etsu (King) and the Nupe kingdom became an ally to Igala.

Traditional patterns

The Igala are patrilineal and authority in the family or clan resides in the men. Patilineality among the people inexplicably entails virolocal residence in which the woman moves into her husband’s household among his paternal kinsmen, or sometimes his maternal kinsmen. The basic family unit is the nuclear family, made up of a husband, his wife and their children, as well as attached kin but rarely did you find this type of arrangement for the traditional Igala society was basically polygamous.

Prof. Doris Laraba Obieje (Nee Adejoh) now the 2nd Female Professor

(known) in Igalaland after Prof. Jummai Ogbadu. Doris is a Professor of

African French Literature, currently at the Great Ahmadu Bello

University, Zaria

As farmers, the need for more hands on the farm meant that men married more wives so that they could raise more children whose help was badly needed on the farm. Besides, in some parts polygamy was a status thing and reflection of a man’s wealth. The more prevalent was the compound family in which you had a man, his wives and children. The nuclear and compound families are, in real sense, units of the wider and longer-lasting patilineal joint family which typically comprises two or more generations of brothers and sons, and their wives and children. In this way Igala families are long-lasting and self-perpetuating as the death of a member makes no difference to its overall structure. It can last over several generations with a membership of up to 100 or more.

Igala couple

An Igala lineage comprises several extended families- the wives and offspring of brothers as well as wives and offspring of the father of these brothers and all the relations of the brothers of ones father.

The clan is made up of several patrilineal related extended families or lineages and has numerous functions, including common name, and identity, exogamous marriages, property ownership, mutual economic and political support and protection from a rival or aggressor among others. As kin who have claim to a common ancestry, they recognize various ritual prohibitions, such as taboos on certain foods, totem etc, that give them a sense of unity and distinctiveness from others.

Kinship relationship

The concept of kinship flourishes well among the Igala. It has helped to construct groups that have lasted for generations and in which the close-knit ties of kinship provides powerful links through the notion of common “blood”. And by claiming exclusive ancestry these groups can claim exclusive rights to clan and lineage property. This kind of kin relationship also provides for individual members a sense of personal identity and security. In traditional Igala society, kinship relationship plays important roles in the lives of the people by determining what land they could farm, whom they could marry, or have sexual relationship with, and their status in the community. It also means much more than blood ties or family or household. It includes a network of responsibilities, and support in which individual families are expected to fill certain roles and obligation.

Among the Igala generic terms such as ‘uncle’, ‘aunt’ or ‘grandparents’ are often not sufficient to describe family relationship, rather very specific terms such as my “maternal uncle” or “maternal aunt” are used to clearly differentiate between patrilineal and matrilineal kin. Lineal relationships, which refer to those between grandparents and grand children, are well cherished. Relationships with uncles and aunts, cousin and nephews and nieces are essentially treated as those biological relatives. The Igala enjoys robust relationship among the maternal kin. As a “daughter” he/she is loved, protected and enjoys lot of privileges but the right of inheritance is only with the paternal clan. Kinship relationships and obligations toward lineal, collateral and affina l kins (i.e between parent –in-law, children-in-law and sibling-in-law as well as with partrilineal and martrilineal kin) are related to lines of descent, to residence, to inheritance of property, to marriage etc.

Igala newly wedded couple dancing at Idah, Kogi State, Nigeria

Incest taboo

Incest taboo refers to any cultural or norm that prohibit practices of sexual relation between relatives. Relations with clan members are permissible where no traceable genealogical relations exist, but members of different clans cannot have sexual relationship if there exists blood ties. The restrictions on marriage and sexual relation amongst kin in Igalaland is based on normative sense of decency and the unequivocal belief in the sanctity of blood ties. There are rules, though not written concerning appropriate and inappropriate sexual relation. Incest, which is sexual intercourse between individual related in certain degrees of kinship, is prohibited. If a man conducts inappropriate sexual relationship with a kin, it is believed that both will suffer severe afflictions from which they would not recover until they confess and the gods are properly appeased through sacrifice. It could also result in barrenness. Both would lose respect among the people as people will no longer take them seriously. In the past young girls involved in such acts hardly ever marry.

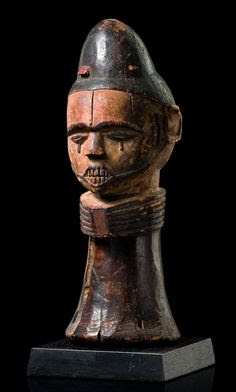

Dance crest "ojegu" from the Igala people of Nigeria | Wood with

polychrome paint || The Igalas principal cult "egu" is connected with

the ancestors who are remembered during yam harvest. The "egu" (spirit

of the dead) is represented by masks and headdresses called "ojegu".

Among the Igala, people relate to one another in different ways, and sometimes distantly, are classified as sibling, and other who are just as closely related genetically are not considered family because they are patrilineal and children belong in the father’s clan. As a consequence of patrilineality relations between brother/sister, father/daughter, mother/son, uncle/niece etc are considered incestuous, though in certain matrilineal society father/daughter may not be such a problem. Sexual relation between a man and his mother’s sister and mother’s sister’ daughter are considered incestuos. Similarly, a man and his father’s sister cannot have a flirtatious relationship, have sex and marry, not even with his father’s sister’s daughter.

Helmet mask "ojuegu" from the Igala people of Nigeria | Wood

Religious belief

According to Professor Emmy Idegu, Igala cosmology hinges on three worlds – efi’le (the world of the living), ef’ojegwu (the world of the dead) and the space inhabited by the supreme being (odoba ogagwu, ojochamachala). A typical Igala person believes in “Ojo” (God) as the Supreme Being. The concept of God is therefore not foreign to the Igala mind. The belief in Ojo-ochamachala (Almighty God who is regarded as Alpha and Omega) precedes the advent of the missionaries. God (Ojo), the Supreme Being is also known by his attributes as creator, as the immortal, omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, unique, transcendent judge and King. They also believe in divinities and spirits.

Okega carving, Igala people, Nigeria, 19th C.

The traditional Igala person believes in divinities or deities who are said to be next in hierarchy to the Supreme Being. Such are personified in certain natural forces and phenomena, especially in rivers, lakes, trees, the wind, deserts, stones, hills e.g. Aijenu (Water Spirits), Ikpakacha (spirit husband), Ane (earth goddess), Ichekpa (fairies or bush babies), Ejima (twins), Egbunu (goodluck), etc. In their order of ranking, the next is belief in deified ancestors (Ibegu). This refers to the spirits of elderly members of one’s family, lineage or society that died non-violent or non-evil death and have promising offsprings. The Igala person believes too in mysterious powers, which come in various forms such as incantations (ache), medicine (ogwu), magic (ifamfam) and witchcraft (ochu, ogbe).

Three basic elements of worship are easily identifiable, namely, Sacrifice, Music/ dancing and Prayer; certain people are regarded as Sacred e.g. family heads (elders) village heads or town leaders i.e. the traditional rulers, who most often act as chief priests before traditional shrines; they also believe in Oracles or divination e.g. Ifa-anwa (by seeds), ifa-ebutu (by use of sand), ifa eyo-oko (by cowries), Ifa-omi (by water).

While making these sacrifices, as earlier mentioned, certain victims or materials are used for sacrifice. These include, food Stuffs or Crops (amewn egbaru) e.g. maize (akpa, igbala), yam (uchu), kolanut (obi), beans (egwa), rice (ochikapa), beniseed (igogo) etc; birds, e.g. hens (ajuwe), chicks (ebune), cocks (aiko), pigeon (oketebe); Animals e.g. She-goats (ewo-ole), she-goats (obuko), ram (okolo), cow (okuno), tortoise (abedo or aneje), agama -lizard (abuta-oko); and some liquid substances e.g. cold water (omi eruru), local liquor (burukutu), gin (kai-kai),and palm-oil (ekpo oje). Other items also employed could be articles of clothing, pieces of white, red or black cloths, money, especially coins or cowries, red feather (uloko), alligator pepper (ata), etc.

It is noteworthy at this juncture that there exists other aspects of the culture which posses certain dynamics or key values that are hinged on some of the above practices. Among them are: Child-bearing and the male-child Phenomenon (fecundity or fertility cults); Naming ceremonies, circumcisions (amonoji); widowhood practices redolent with so much oppression, deprivation, discrimination, rejection, humiliation, abuse and injustice; “ikpakachi” (spirit husbands), high bride price, arrangee-marriages, levirate marriage (oya-ogwu); second burial (ubi) rites; masquerade cults; coronation and initiation of traditional rulers etc.; the issue of caste system or descendants of slaves (amoma adu); use of charms; incisions, oath-taking, rain-making, or reincarnation rites; traditional festivals; etc.

Some of the cultural or traditional practices mentioned above have gone extinct in some areas of the land, but are still so prevalent in many other places. However, there are many other practices which may not be directly related to traditional religion but which are values which need to be cultivated, cherished or modified with all sense of commitment. Such values include the use of Igala proverbs, myths, legends, language, sculpture, greetings, (including tribal marks, tattooing, body decoration), cuisines, discipline, dressing and agriculture.

Source:http://fidelegbunu.com/node/44

THE NAMES AND ATTRIBUTES OF GOD AMONG THE IGALA: A SOCIO-THEOLOGICAL INVESTIGATION

Introduction

This work dwells on the names and attributes of God (Ọjọ) among the Igala people of north-central Nigeria. It is an endeavour to unravel the proper meaning of Ọjọ,

the Igala personal name for the Supreme Being. Other

descriptive/attributive names of God are also brought into cognizance.

The socio-theological import of the use of theophoric names for

children, and as embedded in wise-sayings and proverbs, which are means

by which the Igala person expresses his/her understanding of God are

also dully examined. The research aims at bringing to the fore the

socio-theological understanding of God as reflected in these

expressions.

Ọjọ as the Name of God

In

his article, “What is in a Name? The Philosophy of Naming in Igbo

Culture,” Ekwunife (1996, 2) opines that “scholars on African culture

and religion rightly observe that for Africans, names are not mere

labels, rather, they are pregnant with meanings.” This is also quite

true in respect of the Igala people. The names and titles they give God

are of deep meanings. Such names have meanings that portray what people

think about him (Egbunu, 2009, 74). Most of these names are as old in

origin as the Igala race itself.

As

Mbiti (1975, 42) stresses in relation to many African language groups,

“The personal names for God are very ancient, and in many cases their

meanings are no longer known or easily traceable through language

analysis.” The Igbo (of southeastern Nigeria) linguistic group, for

example, is faced with a great deal of controversies in tracing the

personal names of God. For example, there is argument as to which of Chineke, Chukwu, Chi, Osebuluwa is

original to the language (Metu 1999, 46-57; Njoku 2009, 16-25; Abanuka

2004, 1-43; Iroegbu 1995, 359; Oguejiofor 1996, 5). The Yoruba of

southwestern Nigeria simply refer to God as Olodumare or Olurun (Idowu 1996, 1-2; Awolalu 1979, 3-12) while the Tiv of north-central Nigeria call him Aondo. The Idoma, also of north-central Nigeria, call him Owoicho. For the Bassa Nge (also of north-central Nigeria), God is Soko while for Bini people of the southwestern Nigeria, God is Osenubua.

There are a thousand-and-one names for God in different African

languages. Some are simply personal names while others are descriptive

attributes of God (Mbiti 1975, 43). These names indicate how profoundly

rich African peoples are with ideas on God.

Among the Igala, God is given various names, foremost among which is the three-letter word Ọjọ, the meaning of which seems a bit obscure. Ọjọ,

unlike the other titles and names of God to be examined later, is a

bi-syllabic word within which is embedded everything about God’s nature

and activities. It is significant to note that this name is not an

attribute. It is simply a nomenclature by which the Supreme Being is

known and called by the Igala people from time immemorial. Ọjọ - a sharp word of light and double vowels (Ọ-Ọ) on both sides of a single consonant (j) – can be spelt only in one way, Ọjọ.

Thus, quite unlike many other African languages whose names for God are

derived from compound names or attributes, this name is God’s direct

name. In a nutshell, he does not derive his name from anything else but

all other beings or creatures derive their names from him.

In

our bid to unravel its meaning, we discovered a lot of nuances in its

layers of meaning in relation to other expressions in the language.

Thus, Ọjọ which means principally, the Creator, Owner and

Sustainer of all that exist both in heaven and on earth, or Supreme

Being, could also be related to certain expressions derivable from the

Igala language. As a matter of fact, there is a sense in which one may

say that phrases such as the following are connected to the activities

of God:

Okwujọ – equality (in God’s sight, all humans are equal); Ichẹ chejọ – it was made and kept (in the mind of God existed all that were created); Ichẹjọ – it’s complete, perfect in totality (in God alone is found perfection); Ọjọ duu – everyday, both night and day (God is ever ready, active and watchful); Ọjọ nwa – Day break (in God is the dawning of all good things); Own jọ –

God is He who is ever there, who exists in many ways in nature itself,

and is pre-existent. In another sense, God is one who is more than any

multitude or crowd. Put differently, the sense expressed here is the

fact that Ọjọ chawuli (God is spirit) in which case the air and

wind are often used as metaphors when people see or feel the effect of

the air, but they do not see the air or wind itself (Mbiti 1975, 53).

In the name Ọjọ,

therefore, the preexistence of God is manifest. His existence is also

taken for granted by the Igala. There is no coherent Igala legend or

myth on the origin of Ọjọ. Any attempt at forging one is

self-contradictory. The Igala people believe that He has neither a

beginning nor end, but that He is self-existent. He is just there from

nowhere and to nowhere as such. He owes His being to nobody and is

answerable to nobody else.

Embedded within the meaning of the name Ọjọ in

Igala language is the idea that he is the self-existing Being and the

source of all things. He is constant, unchanging, stable and reliable,

incomparable and unsurpassable in majesty and excellence. And hardly is

there any symbolic representation of the Supreme Being among Igala

people. What Idowu (1996, 33) observed on God in Yoruba culture is very

much applicable in the Igala case: Ọjọ is “perfect in superlative qualities.” Certain attributes of Ọjọ are directly connected to the meaning of Ọjọ as explained above. Thus, He is called Ọjọ-Odobọgagwu,

which means, incomprehensible, unpredictable and all-surpassing Being.

This name is a combination of four words which are major attributes of

God, namely Ọjọ, Odoba, Oga and gwu. Having given some clarification on Ọjọ thus far, we will now simply turn to the other three attributes. Odoba is a combination of Odo (habitation) and ba (short form of bailo which means frightfulness). Rendered fully in Igala, it is expressed as Odown abailo (His presence is awesome). Oga means giant, leader, ruler or head; while gwu means ‘seated’ or ‘enthroned.’ Odobọgagwu therefore means that God is depicted as the head, ruler most powerful and incomparable one. Thus, Odobọgagwu holds

the Igala understanding that all reality in its totality is ruled by

God who apportions to each person his/her destiny. All this goes to show

that the Igala person conceives of God as an absolutely perfect Being.

We may now dwell on some of his basic attributes so as to bring to the

fore salient points on His nature.

The Basic Attributes of God

Iroegbu’s

(1995, 115) categorizes God’s attributes into the entitative, operative

and transcendent. According to him, the entitative attributes, describe

God as simplicity par excellence, without limit or

frontiers, unique, invisible, unchangeable, eternal, omnipotent,

omniscient, omnipresent, impassible, all-good, all-merciful, etc.

Operatively, He is seen as being of infinite intelligence, voluntareity

and the uncaused cause (as Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas would have it).

In His transcendental attributes, God is manifest in His qualities of

distinctiveness, exemplarity, order or beauty in their perfect form. In

Igala perspective, this is similar to referring to God superlatively in

many ways such as Ọjọ-ọdẹ ma (the Master of all existent beings); Ọjọ-otemeje (Great God); Ọjọ-Ọgbẹkugbẹku (Supreme); and Ọjọ-Ọdafẹ onu inmi (Master of life).

As the attributes try to portray, it is He who owns human breath and He

gives breath. This is in line with the myth that says that in the dim

past, God who is “Abucha ki n’ọda ama” (the potter who fashions

the clay as he so pleases), in His creative ability, breathed into the

hollow image of man which He had fashioned from “ebutu” (dust). Thus, He created both the beautiful (abo) and the ugly (ikaga). He it was who created the different sorts of human beings, the ejima (twins), ọdi (dwarf), ẹnẹfu (albino), abuke (hunchback), adọwọ/dẹrẹ (the lame), ẹnọlọ (the handicapped), ajalu (dumb), ajeti (deaf), afeju (the blind), etc.

God is called Ọjọ - ọchamachala (Ọmachala)

in so far as He is the one who has no equal, namesake or rival. The

whole world is His flowing garment. He is limitless and capable of doing

anything He pleases. He is also called Ọjọ-olichoke (nebua),

that is, God is like the umbrella tree for the entire humankind and, of

course, bigger than any mountain. His decisions for mankind are quite

perfectly good and unalterable.

God is Ọjọ-achọna (architect) since He is known as the creator, artist and great builder or designer par excellence. In this same vein, He is referred to as Ọjọ-abucha (Ki n’oda ama) – the potter and designer of human destiny. He is Ọjọ-olugbọna (agejefu kia g’ọdọda)

in so far as He sees both inside and outside simultaneously. To Him,

nothing is hidden. He has an all-seeing eye. In this light, He is also Ọjọ-agefu (kilẹ agalu) who sees or knows all human intentions while the world specializes on the external.

God is also known as Ọjọ-agbẹnẹ – the one who saves; Ọjọ anẹ m’agẹdo – the one who has no iota of fear; Ọjọ-onu – God who is the king; Ọjọ kin’ilẹ – the Creator of the universe; Ọjọ ohimini lẹi lẹi –

whose ways are so deep and unimaginable. He is, as a matter of fact,

larger than life and mightier than all the oceans in the world combined.

The list is simply inexhaustible (Egbunu 2009, 74-75).

In analyzing the meaning of the attributes of God, the name in itself, Ọjọ,

without any epithet, carries with it a lot of significance. However,

the epithet or appellation specifically defines concretely the idea

being bandied. It is most often, self-explanatory. It is noteworthy

that Ọjọ is the more ancient and common name used by everybody

in the land. But in addressing the superlative greatness of the Supreme

Being in different circumstances, other appellations are employed or

added. For instance, Ọjọ Ondu (or odu) means God, the Master. It could be said to be an abbreviated form of Ọjọ Onu-ibo-duu (God, the overall king or what a typical Igala means when he/she exclaims “Ọjọ Odu-mi-onu!”

(“God, my master and king”). Such attributes are inexhaustive. Some of

them are found within names given to children and even in innumerable

wise-sayings. Here, we present a simple taxonomy of such names.

Agana

Theophoric Names and Proverbs Reflecting Attributes and Activities of God

In

certain circumstances, Igala parents give theophoric names to their

children which also reflect their understanding of God. An individual

may bear one or more of such names. Some examples might be necessary at

this juncture. Ọjọ-ninmi, for instance, denotes God as the

author of life. This reminds parents and relatives of the saving grace

which sustains the life of such a child. It is also explainable in

relation to death. That God the giver of life is the only one who is

capable of restoring it in times of chronic ill-health. That is why the

name Ọjọchogwu is also given to other children depicting God

himself as medicine or remedy to every ailment. This same God can also

decide to take this life when and if he so pleases. Ọjọtule is

yet another name which is also very meaningful. In this sense, God is

greater than all. No matter what humans may conceive mischievously, only

God’s designs must take preeminence. His verdicts are final. God is

seen here to be ever triumphant or victorious. He is often referred to

as Ọjọ anachẹ (He who is able) and Ọjọ agbẹnẹ (whereby the name, Ọjọgbanẹ holds a lot of significance). That is, he is savior at one and the same time. The name Ọjọ dọmọ which

means God exists, and that he really exists, captures the idea of total

resignation to God in the face of challenges of life. It is explainable

in view of the fact that God never sleeps (Ọjọ alolu n). This expresses God’s care, ever-abiding presence and guidance (Ọjọchide, Ọjọago). Also related to this is the symbolism of Ọjọ oli abẹnga (God who is symbolically referred to as a fork-stick or great support). He is very much in control and his glory (Ọjima Ọjọ) reigns supreme over all the earth. Ọjọ agefu is

yet another name that has deeper meanings. This especially connotes the

fact that God searches the mind of man even when humans judge from the

externals. It is a way of stating categorically that clear conscience

fears no accusation. It is God who really possesses the truth (Ọjọ nọgecha).

In this case, while we live in a world filled with so much falsehood,

God is seen as the only one who can be relied upon to reveal the truth

and who keeps his covenant ever in mind. He also directs his chosen ones

to the truth (Ọjọ anonẹ le). Ọjọma emphasizes the

fact that God knows everything and that nothing is ever hidden from the

all-seeing eyes of God. He is all-knowing and wisdom personified (Ọjọnuma). Ọjọgbene has

to do with the questioning mind of man when faced with the vicissitudes

of life. If men were capable of asking God the multitude of questions

in their minds, which would require God’s immediate response, such

questions would have flooded the divine throne. EleỌjọ is yet another name which holds a lot of significance in the Igala understanding. Children are seen as God’s gifts par excellence. It is God who actually owns children (Ọjọnẹ, Ọjọnọma, Ọjọduwa, Ọjọka, Eikọjọnwa). And it is he who is seen as their creator (Ọjọnyi and Ọjọchọna).

It is with this mindset therefore, that children are not expected to be

rejected or despised. They are rather supposed to be well-catered for

and nurtured unto maturity.

Similarly,

the Igala have proverbs which bring out profoundly the nature and

attributes of God. Some of them are discussed here: Ọjọ akajọ ọkpakpa – God is a just Judge; Ọjọ atẹnẹ achi (kial’ẹnẹ ọkpẹ) – God removes one’s calico and clothes one with the shroud or linen; meaning, it is God who decides man’s fate; Ọjọ akpẹnẹ adu makọ– God is the one who does not take no for an answer; it also means no one can question or challenge God; Ọjọ akabẹlẹ kiachabalẹ – God is the one who promises and fulfils; Ọjọ mali ẹwn kalu ajẹn yanwan – Providence rises before the Sun; (tomorrow takes care of itself); Abọjọ nyẹnẹ onwu ẹnẹ adẹ – No man can really change his destiny; Ọjọ ki nyabo onwu nyikaga – God created both the beautiful and ugly; Ẹnẹ ọgẹcha Ọjọ atọbi – The just triumphs; Ifitumi ki ma fi r Ọjọ – Nothing puzzles God. Or, with God, all things are possible; Ma bi’ọjọ ọlan – God is blameless; Ọjọ achodudu alon – The morning does not last whole day long. A variation of this is: A stitch in time, saves nine; Ọjọ adonẹ jonu – Human elevation is of God; Ọjọ ajogwu kebutu makwu – God’s battle raises no dust; Ọjọ kidu ki ma nwan Ch’ọjọ eche onwu iche – There is always light at the end of the tunnel; Ọjọ kidẹnyọ wa, Ọjọ mugbo kẹnyọ dẹ – The God who originates good fortunes knows how to bring them to fulfillment; Onẹ akọla ina diba w’ọjọ – Don’t be self-conceited; give God his sway; Onuchẹ Ọjọ ya ma ọna ulẹn – One in the service of God is protected; Abu nacho, abu na ma, eikibọ dọwọ ọjọ – No matter how skillful you are, you depend on God for perfection; Ẹwn duu maja nw’ọjọn – Nothing is hidden from God; Ọjọ kọbọ hiugba onwu omi alọ – it is when it is the turn of the unfortunate person that abnormalities abound.; Ọjọ kuma bucha onwu ma nyucha alu – There is time for everything. Variation: A stitch in time saves nine; or make hay while the sun shines; Ọjọ mu nwa r’ochu imudone – When a witch is exposed, she turns into a plaything; Ọjọ n’ọmẹmẹlẹ – God determines all goodness; Ẹla ki ma n’otiyi n, Ọjọ anachichi-wn – The tailless animal has God for its most pressing needs; Ẹnẹ ku ma kọ, Ọjọ mugba – The rejected stone has become acceptable to God. Variation: the rejected stone has become the headstone of the corner; Ẹwn ki defu akele ki kp’ọcha, Ọjọ ki jẹ kijẹ – May our good wishes be fulfilled; Ọjọ ohimini – lẹu lẹu, abu echohimini kia dabu? – Oceanic God, the inexhaustible God; Ọjọ alolu ẹnẹ anọma – If God sleeps, who caters for His children; Ọjọ amẹnẹ ki ma n’ikwu –

God who catches criminals without using rope. Variation: God works in

mysterious ways; or He writes straight on crooked lines; Ọjọ chema taki ch’ala igba – God knows why the sheep is bereft of horns; Ọjọ ch’ogwu ta kogwu ch’ọjẹ ọga – God is the architect of the medicine that heals. Variation: we care but God cures; Ọjọ gbanẹ ta k’ogwu ch’ọga – When God desires to sustain someone, medicine becomes efficacious; Ọjọ d’Abẹdo timoto ta ki ajadu ibẹchi – When someone’s luck begins to shine, it would seem like skillfulness; Ọjọ gw’ata tak’ata gw’ọma – It’s when God favours the father that it tinkles down to the children; Ọjọ jọ y’agbogwun – When death beckons, medicine is no remedy; Ọjọ kare m’onu ẹwẹ onwu ma m’ọya ufẹdọ – It is in the day of adversity you know who really cares; Imabẹn ẹmẹnẹ ki ayọn – If all is well with you, you hardly know your enemies; Ọjọ kate malu komi le ki w’efu unọba – Certain secrets are known to God alone; Ọjọ kẹ gbei onẹ onwu ẹgbei ola wẹ – One good turn deserves another; Ọjọ ki jẹ kẹ lekwu neke kponẹn – A mere death-wish cannot kill; Ọjọ ki makwu ma r’akwu bọ – better cry to God who knows the depth of human predicaments.[1]

As

can be readily gleaned from the above proverbs God’s nature dovetails

into His activities but His attributes are clearly manifested in all of

them. In a very brief manner, we shall pinpoint some aspects of the

above investigation with which have social and theological implications.

Socio-Theological Reflections

A cursory reflection on the above names or attributes of God which are

replete in the various forms of proverbs and appellations in the

day-to-day life of an Igala, draws home many crucial points.

As a matter of fact, all those attributes which express his

omnipotence, supposedly address the overarching nature of the existence

of Ọjọ as the Supreme Being. This explains why the typical

Igala would see God as being relatively remote. It is with this singular

mindset that the Igala, like many other Africans (Mbiti 1982, 40; Metuh

1999, 20; Awolalu 1979, 16; Idowu 1996, 40) approach God through lesser

divinities such as their localized gods/goddesses, ancestors, spirits,

etc. Such deities, including natural or supernatural phenomena are often

considered as intermediaries, agents or messengers of the Supreme

Deity. When prayers, invocations, incantations, sacrifices and offerings

are being made to appease such divinities or gods, they are done with

the understanding that the Almighty God (Odobọgawu) is being

appeased or worshiped. When and if, for instance, the people are in need

of bumper harvest, blessings of the womb, job opportunities, victory

over enemies, progress in all ramifications, peace with neighbours, it

is this self-same God (Ọjọ) who is approached through the divinities/ancestors. Even Igala festivals such as Ibegwu, Anẹ, Ọgani, Egbe, etc which are celebrated according to their different local seasons, are tokens of gratitude to God (Ọjọ)

the Supreme Being, for the gift of life and one another, also as means

of purification of the people and the land. Or rather, as the case may

be, such festivals are celebrated as avenues for breakthroughs and/or

divine favours. They are also done with the mindset of not only

worshiping Ọjọ through such deified ancestors or spirits, but

with the aim of practically seeking God’s intervention in human affairs

(Egbunu 2001, 33; Egbunu 2010, 41). Ultimately, Ọjọ owns the

human breath. When he decrees death, there is no appeal, and when he

gives life, no human can take it. This explains why even the medicine

man calls on God Almighty before ever he takes any step in the process

of healing the sick or delivering the tormented person.

Besides, it is believed among the Igala that the destiny of every

person is allotted to him or her by the Supreme Being. In this case, the

doctrine of predeterminism or predestination is understood in its

moderate sense that God predetermines every person’s destiny in life

through the type of Okai (spirit guardian) designated unto him

or her. This, however, does not preclude anyone from being personally

responsible for whatever action or inaction his life is involved in, for

good or ill. The human person is said to be responsible for whichever

direction his life assumes. In other worlds, every individual shall be

accountable on the day of reckoning in the life-after-life. This would

either be in relation to how such a person would reincarnate or the mode

of existence that would be meted out to such a fellow in the hereafter.

Among the Igala, there is a profound respect for human life. Human life

is held as sacred from birth to death. As such, even the soul of the

“unborn” child is never toyed with, lest one be made to face the wrath

of the ancestors/divinities. Ọjọ is considered as the just

Judge before whom every being amounts to nothing. Put differently, none

is greater than God the Supreme Deity. This alone holds the secret

behind Igala exercise of great patience, endurance and resilience in the

face of all forms of awkward challenges of life.

The Supreme Being (Ọjọ)

is said to have created everything in the universe including man. To

Him, therefore, every being must be subservient. It is believed that He

is unquestionable and as such, He alone possesses the reason for

creating things and people differently. Discrimination, subjugation,

oppression or arbitrary treatment of fellow humans on the basis of

inequality is thereby not only seriously frowned at and highly detested

but punishable by God in the hereafter. Killing of twins or triplets,

dwarfs, albinos, and the like, is totally abhorred. So it is also that

it is recognized profoundly that humans are made male and female. In

this light, every gender is treated with utmost regard. While men are

expected to accord women due respect, bearing in mind the socio-cultural

import of role-sharing and role differentiation, the women are also

expected not only to reciprocate but to play the complementary role. The

“Live and let’s live” principle in the relational setting of a typical

African (Egbunu 2009, 132) setting is given pride of place. It is by

this token that unnecessary violence in the society and threat to the

life of fellow humans, is to say the least, highly reprehensible.

Conclusion

Apparently, this study has been able to unveil to some reasonable

extent that the Igala people are very rich in their ideas about God. The

nature, image and names of God in Igala tradition and culture are of

great significance. Their thoughts on God are completely embedded in

their beliefs and customs. The name which they give God, whether as a

description or as personal names belie their understanding of Him. Their

proverbs, parable and anthropomorphic images convey some outstanding

message that God is superlatively greater than anything that can be

thought of or imagined. The résumé lies in the fact that Igala people

generally conceive of God as an absolutely perfect Being. And it is this

“Ọjọ” the Supreme Being that explains the reality of every other being. It seems plausible therefore to believe that “Ọjọ”

among the Igala people is a mysterious Being whose being alone solves

the puzzle of the existence of every other being in the entire universe.

Little wonder then that the social life of a typical Igala person is so

much so coloured and shaped by his/her theological understanding of the

inalienable place of God in human existence.

PERSONHOOD (ONẸ) IN IGALA WORLDVIEW: A PHILOSOPHICAL APPRAISAL

Journal of Cross-Cultural Communication Vol. 9, No. 3, 2013, pp. 30-38

PERSONHOOD (ONẸ) IN IGALA WORLDVIEW: A PHILOSOPHICAL APPRAISAL

EGBUNU, FIDELIS ELEOJO

Phone Number: 08068515750 & 08059215672

E-Mail Address: frfidele@yahoo.com

DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES, KOGI STATE UNIVERSITY, ANYIGBA, NIGERIA

Abstract

Personhood in

Igala worldview dwells on the centrality of the human person in the

universe. The Igala understanding is employed as a launch-pad unto the

general African perspective on this all-important discourse. Using the

hermeneutical, descriptive and analytical methods, the people’s

worldview is sieved from some of their traditional and cultural beliefs

and practices as the Western classical philosophical ideas and some

basic African thoughts are brought to bear on our subject matter. While

attempting to posit a sound basis on the Igala ontology of Being in line

with certain yardsticks, they proposed in defining the human person,

the concept of solidarity and communal living is presented as a crucial

desideratum in any meaningful reflection in this respect.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCTION

This paper is a modest attempt at considering the concept of personhood

in African Philosophy with the Igala worldview in focus. Naturally, a

few pertinent questions such as, who or what is a person (onẹ) in the Igala understanding? What does personhood (onẹ)

entail in the African, nay, Igala worldview? What is the philosophical

basis of Personhood? How do Africans generally see the human person in

relation to the community? What is the Igala ontology of Being? Is it

every type of human being that is considered to be a person? Or rather,

are there certain qualities or characteristic yardsticks associated with

a “person”, as such? What are those yardsticks? Does this particular

conception of personhood in Africa have a corollary on a general basis?

In the course of proffering solutions to these posers, the relationship between the community (Udama) and Personhood (onẹ)

shall be largely explored, using the analytic method. This is expected

to lead us to a fuller understanding of personhood in our context.

ONẸ ECHE (PERSONHOOD, WHO AND WHAT IT ENTAILS)

The concept of a “person” (onẹ) in Igala mind-set has different layers of meaning. First, “onẹ”

literally translated in Igala means person or human being. That is,

anybody identified as a human being in contradistinction with animate or

inanimate objects.

Second, is “onẹ” as one who has come of age. This is in relation to physical maturity or psychological well-being.

Third, is “onẹ” in relation to some traditions whereby certain individuals in the society are considered “free-born” (amọma onẹ i.e. literally offsprings of “persons”) in relation to other sets or groups of people termed descendant of slaves (amọma-adu) in specific areas of Igala land.

Fourth, is the description of “onẹ”

as a fellow possessing many virtuous or forward-looking qualities. It

denotes the exhibition of a couple of such positive or promising

characteristics which his relatives, friends, acquaintances or neighbors

would be generally proud of. Qualities such as ability to live amicably

with others, being amiable, harmonious living, peaceableness,

tolerance, patience, gentleness, loveability, trustworthiness,

transparency, truthfulness, courage, temperance, modesty, intelligence,

kindness, generosity, compassion, dynamism, resourcefulness,

progressiveness and a generally attractive and magnetic life are

considered as the yardsticks.

This very last category of personhood in Igala understanding which

entails virtuous living in all its ramifications is largely our point of

reference in this paper. As it were, the aforementioned characteristics

readily bring to mind the need for unity, co-operation, togetherness,

etc.

The varying layers or degrees of Igala worldview of “onẹ” simply implies why a typical Igala would exclaim, “ẹfonẹ li ib’ema”

(knowing somebody goes deeper than ordinary sighting). In other words,

“it is not all that glitters that is gold” or better put, “you cannot

judge a book by its cover.” It is in this respect that even though one’s

physical stature or status or name may contribute to defining who one

is, one may not judge the quality of a person just by such mere

considerations. In Igala worldview, for instance, it is believed that “odu ch’ajamu onẹ”

(name is the bridle and bit for controlling a person), a name can make

or mar a person’s entire life. It is in this sense that a typical Igala

would hold that “odu nyọ tọkọ le” (good name is to be preferred to money).

It is of utmost significance that it is the society or community that gives name (odu) to a child before that particular human person assumes his God-given space in the community. Obi (2008, 199) in his Philosophy of Names harped

on the fact that even though a name “moulds” and “cuts” one’s “separate

identity” the person may not necessarily be reduced to the name since,

reducing a person to the status of a name appears degrading as names are

not conscious of themselves. In a nutshell, the human person is not

confined to behaving in line with his name. He has the capability of

choosing to have his behaviour at variance with his name. However, as it

is often stressed, “without it, a child remains a nonentity since his

name defines his personality in a community” (Ekwunife nd., 37), “names

are part and parcel of those elements of African culture that go to make

African personhood unique.” (Umorem, 1973), they are capable of

fashioning out his unique identity (Iwundu 1994, 57; Ehusani 1997, 131).

This carries with it a lot of social implications. In the course of

searching for a marriage partner or business partner, for instance, it

is not just the mere appellation that matters in considering his or her

suitability, the person as such (in totality) is brought into focus. The

family background, the person’s social habits or traits, economic

status, religious tenets, political leaning, emotional maturity,

educational background, and much even much more, form part of the

yardsticks. There is a sense in which whoever is considered as not being

a person in the above light is denied marriage-partner, land or some

business connections. It is noteworthy too, that unmarried and childless

adults are said not to be full persons. We shall at this juncture pry

into the classical philosophical basis of personhood.

PHILOSOPHICAL BASIS OF PERSONHOOD

Personhood is a derivation from the word “person” which literally means “an individual human being” (Chambers Dictionary 1999,

1033). It denotes the condition or state of being a person. Runes

(1997, 229) defines person in Max Scheler’s terms as “The concrete unity

of acts. Individual person, and total person, with the former not

occupying a preferential position.”

In

Scholasticism, Boethius (475-525 AD) defines “person” as “an individual

substance of rational nature” (Runes 1997, 229). It refers to the

individual as a material being. Matter provides the principle of

individuation. The soul on its own is not a person. Among the material

beings, man in his composite being is known as person because he

possesses the rational nature. He is endowed with dignity and rights and

he is the highest of the material beings.

The

doctrine of the human being as an explicit theme of philosophical

reflection developed gradually through the ages. Most often, the era of

Ancient Greek and Roman philosophy is mainly known for being

“cosmocentric”, the period of Christian Medieval philosophy as

“theocentric” and the age of modern and contemporary philosophy was

tagged “anthropocentric” (Onah 2005, 161).

Even though earlier philosophers concentrated on the study of the

physical world and God, and not man, the human being was always at the

centre of the philosophical enterprise, though indirectly (Onah 2005,

161).

It

is worthy of note that even though the words, “personhood”, “person” or

“personalism” are relatively modern, the philosophy had existed as

attempts at interpreting the “self” as a part of human experience. These

elements of “Person” are traceable in the philosophy of a couple of

philosophers, such as, Heraclitus (536-470 BC) in his statement “man’s

own character is his daemon”; Anaxagoras (500-430 BC) in his Cosmogony

while emphasizing that the mind “regulated all things, what they were to

be, what they were and what they are” the force which arranges and

guides, giving an anthropocentric trend; Protagoras (480-410 BC) in his

famous saying that “man is the measure of all things” while stressing

the personalistic character of knowledge.

The

philosophy of persons found its highest point in Socrates (409-399 BC)

in Greek philosophy, in his recognition of the soul or self as the

center from which all actions of man emanated. Plato (427-347 BC)

acknowledged the person in his doctrine of the soul. However, he turned

the direction towards dominance by the abstract idea; Aristotle (384-322

BC) insisted that only the concrete and individual could be real.

In

the Christian Medieval Era, St. Augustine (354-430 A.D) held that

thought, and therefore the thinker, was the most certain of all things.

These personalistic concepts were better expressed in the work of Thomas

Aquinas (1225-1274 A.D) who adapted the definition of Boethius, when he

affirmed that the human person is “subsistent substance of rational

nature”. This was followed by an entire array of philosophers in France,

Germany, England, and America. The most prominent among Philosophers in

France was Descartes, who stood gallantly with all others against

Positivism, Materialism and Naturalism under different cloaks. Their

counterparts in Germany also developed personalistic philosophies with

Schleirmacher (1768-1834) taking the lead; in England also appeared many

theistic personalists such as Bishop Berkeley (1710-1796); in America

were others too, such as Bowne, G.T. (1842-1921), J.W. Buckhan (1864…).

Then, other later Personalistic Movements that sprang up (Runes 1997,

230).

As a

matter of fact, “personhood is seen as an ultimate fact” (Mautner 2000,

418) in opposition to the Naturalist reduction of the person to

physical processes. Also against the backdrop of the idealist submission

that the person is merely a transitory, less-than-real manifestation of

the absolute.

In Heidegger’s (Runes 1997, 242) conception of (Dasein),

the sort of being

that I manifest is not that of a thing-with-properties. It is a range of

possible ways to be. I define the individual I become by projecting

myself into those possibilities which I choose, or which I allow to be

chosen, or which I allow to be chosen for me. Who I become is a matter

of how I act in the contexts in which I find myself. My existence is

always an issue for me, and I determine by my actions what it will be…

It is in this vein, Heidegger sees a human being as being essentially a res cogitans –

a thinking thing and that there is nothing which we have more immediate

access to than our own mind and its contents. This would carry a lot of

implications for our understanding of a person. The human person,

therefore, lives in a way that is genuinely self-determining and

self-revising.

Kierkegaard (Runes 1997, 295), the quintessential existentialist’s view

is also very relevant here, according to him, existence is not just

“being there” but living passionately, choosing one’s own existence and

committing oneself to a certain way of life. He decries a situation

whereby a person would just form part of an anonymous ‘public’ in which

conformity and ‘being reasonable’ are the rule, then passion and

commitment the exceptions. He compares existence with “riding a wild

stallion, and “so-called existence” with falling asleep in a hay wagon.

Riccards di San

Vittore sees Person as “an individual being, endowed with a spiritual

nature that is also incommunicable” (Brugger and Baker 1972, 302). In

other words, that “man exists and subsists only through the existence

and subsistence of his spiritual soul”.

Omeregbe (1999, 36) makes a list of six major attributes of a person.

The human person is seen to be “rational, moral, free, social, capable

of interpersonal relationship and possesses individuality because “there

is nothing like a collective person”.

The

word, “existence” employed in a couple of definitions above “already

opens up the modern anthropological concept of a person in relation”

(Brugger and Baker 1972, 302). Here, the concepts of community,

communalism (Ujamaa) and “Udama” (Solidarity) in Igala

are seen as being quite interrelated. This is what Beller (2001, 30)

refers to as “concept of person as “relationality”. This brings us to

the next sub-topic.

AFRICAN PERSONHOOD AND COMMUNITY LIVING

This concept of person as “relationality” as indicated above connotes a

situation whereby the “person exists only by self-accomplishment in

another person, in view of other persons” (Beller 2001, 30). For our

purposes here, the symbiotic relationship between the person and the

community is very crucial in our treatment of the anthropological

connection.

The

“I-you” relationship takes the back seat in this respect, as the “We”

relationship takes pre-eminence. Cardinal Wojtyla’s (in Beller 2001, 31)

essay on “Person, Subject and Communion” in relation to inculturation

brings home this point, “The communion of “We” is this human plural form

in which the person accomplishes itself to the highest degree as a

subject”. Okere (1996, 151) in relation to the Ibo culture opines that

the “self” is congenitally communitarian self, incapable of being,

existing and really unthinkable except in the complex of relations of

the community. It is a web of relations. The human person lives out his

perfection in relation and personhood is therefore attained in relation.

As Menkiti (2011, 173) succinctly puts it, “The African emphasized the

rituals of incorporation and the overarching necessity of learning the